No evidence of sterile neutrinos

There is no evidence for the existence of sterile neutrinos – a fourth type of the elementary neutrino particle. This is shown by the international MicroBooNE collaboration at the US research center Fermilab with the participation of the University of Bern. The results confirm the standard model of particle physics and rule out the possibility that sterile neutrinos are the explanation for certain anomalies in earlier physics experiments.

Neutrinos are tiny elementary particles that played an important role in the early stages of the universe. Although they are among the most common particles in the universe, they are also among the most mysterious. This is because neutrinos rarely interact with other matter – which is why they are also known as "ghost particles". Fundamental questions about the physics of neutrinos are still unanswered – such as how they obtain their mass and what role they play in the fact that there is more matter than antimatter in the universe. Their existence has been known for several decades and three types of neutrinos played an important role in the development of the so-called standard model of particle physics, also known as the "world formula". This model offers an explanation of the universe and describes the smallest components of matter and their interactions. However, earlier experiments showed unexpected measurement results that cannot be explained by the previous understanding of neutrinos. To explain these anomalies, researchers suspect the existence of a previously undiscovered fourth type of neutrino – sterile neutrinos.

However, new results from the so-called MicroBooNE experiment at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) particle physics research center near Chicago (USA) now very probably rule out this possibility after several years of searching: The research group with the participation of researchers from the Laboratory for High Energy Physics (LHEP) and the Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics (AEC) at the University of Bern has found no evidence of a fourth type of neutrino. The results were published today in the scientific journal Nature.

The mysterious neutrino particle

Neutrinos have long been the focus of intensive research. They are created in many places – for example in the sun, in the atmosphere, in nuclear reactors or in particle accelerators. However, as they rarely interact with other matter, they are difficult to detect and are therefore often referred to as "ghost particles". Nevertheless, they can be indirectly visualized and studied using special particle detectors.

Neutrinos can switch between their three types – electron, muon and tau neutrinos – in a special way, which is known as "neutrino oscillation". In the 1990s, an experiment in the USA investigating neutrino oscillations showed more particle interactions than theoretically predicted. A popular explanation for this unusual result was the assumption of a fourth type of neutrino, the so-called sterile neutrinos. However, this hypothetical particle would be even more difficult to detect than its known "relatives" and would only react to gravity. "With the detector technology available at the time, however, neutrinos were less reliable to measure. This is why the idea for the MicroBooNE experiment was born in 2007," says Michele Weber, Director of the Laboratory for High Energy Physics (LHEP) and former Scientific Director of the MicroBooNE experiment.

Precision measurements with the Bernese liquid argon detector

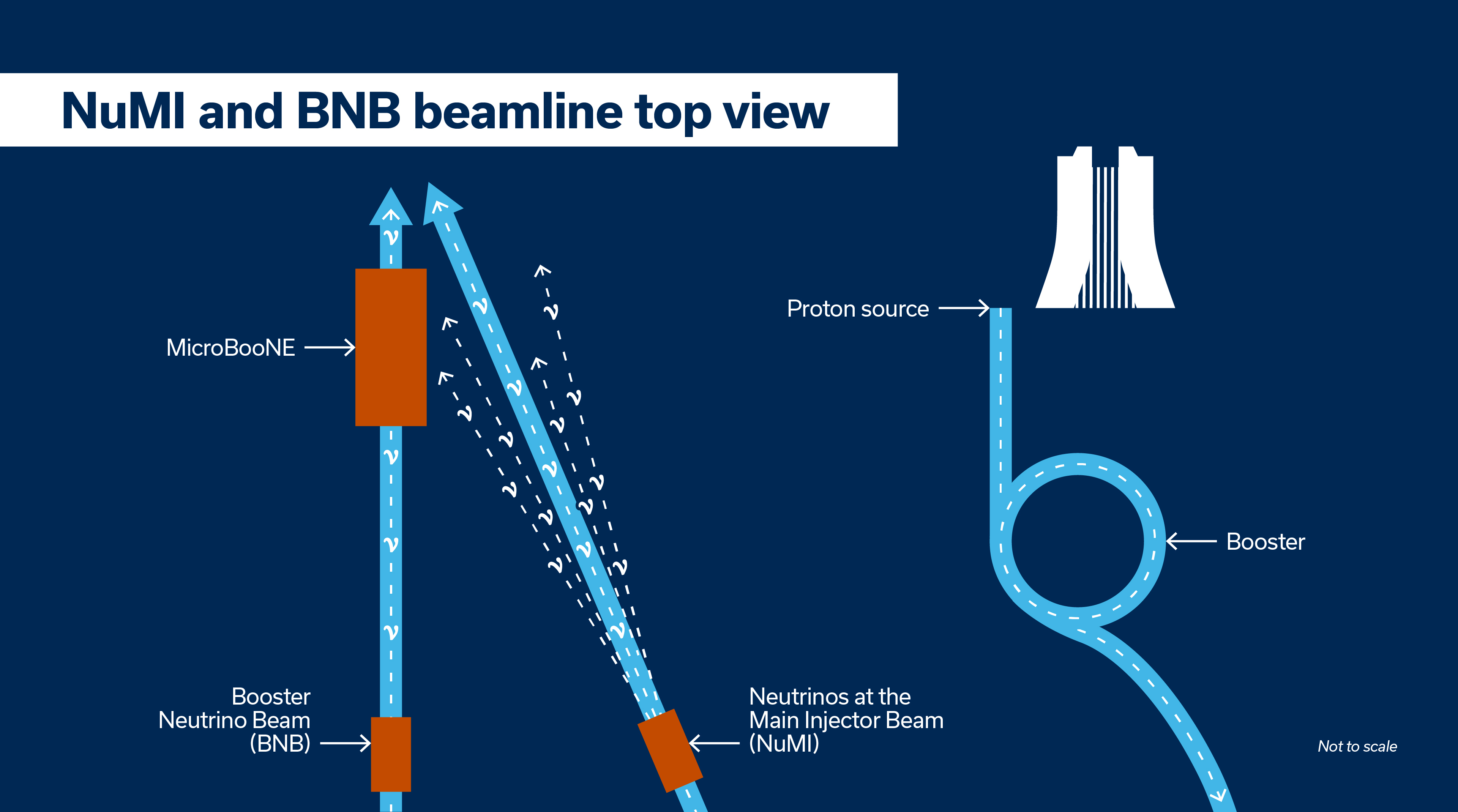

The MicroBooNE detector was used in the Booster Neutrino Beam (BNB) at Fermilab from 2015 to 2021 to test the existence of sterile neutrinos. The detector is located in a 12-metre-long cylindrical container filled with 170 tons of pure liquid argon. The detector also used the NuMI beam at Fermilab. This double beam source enabled the researchers to reduce the uncertainties in their measurements and exclude almost the entire area in which a single sterile neutrino could be hiding. Thanks to the detector, the MicroBooNE collaboration, consisting of researchers from 40 institutions in six different countries, was able to take high-precision 3D images of neutrino events and study the interactions in detail. "The technology with liquid argon was co-developed here at the University of Bern. At times, around ten researchers from the Laboratory for High Energy Physics and the Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics (AEC) were involved in the collaboration and contributed to the development and construction of the detector," explains Weber.

No trace of sterile neutrinos

The latest results from MicroBooNE have now been published and show no evidence of sterile neutrinos. The results are thus in line with the results of the MicroBooNE experiment from 2021. With this new result, MicroBooNE was able to rule out an explanation of the anomalies in earlier experiments by a single sterile neutrino with 95 percent certainty. "A discovery is of course always more exciting, but the results are no less meaningful or significant. They show what modern neutrino detectors are capable of today and definitely answer a fundamental question in physics," explains Weber. "The results will motivate physicists to look for possible further explanations for the anomalies," Weber continues.

Further neutrino research

The MicroBooNE experiment has not only helped to clarify this neutrino mystery, but has also provided valuable insights into the interactions of neutrinos in liquid argon. These findings are crucial for future experiments such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment DUNE at Fermilab, which involves more than 1,400 researchers from over 200 institutes worldwide and uses the same liquid argon technology. DUNE is the world's most comprehensive neutrino experiment. The researchers at the University of Bern are contributing the main component of the so-called "near detector", which is designed to detect neutrinos immediately after their creation.

MicroBooNE has received funding in Switzerland from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics, among others.

Publication details:Abratenko, P. et al. (2025). Search for light sterile neutrinos with two neutrino beams at MicroBooNE. Nature. |

Fermilab and the University of BernFermilab and the University of Bern signed an agreement to collaborate on neutrino experiments starting in 2019. This is the first agreement between a Swiss university and Fermilab, one of the world's leading laboratories for particle physics. The University of Bern's contribution to the scientific collaboration is comprised of three projects: MicroBooNE, SBND and the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), which is considered the topmost neutrino observatory in the world. More about the collaboration between Fermilab and the University of Bern |

Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental PhysicsThe Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics (AEC) was founded in 2011. It’s goal is to foster research and teach fundamental physics at the highest level at the University of Bern. It focuses on experimental and theoretical particle physics and its applications (such as medical physics), as well as associated spin-off and outreach activities. The AEC was founded with the collaboration of the Institute for Theoretical Physics (ITP) and the Laboratory for High Energy Physics (LHEP) of the University of Bern. With more than 100 members, the AEC is one of the largest university groups of researchers in the field of particle physics in Switzerland and a major player at the international level. |

The Laboratory for High Energy Physics (LHEP)The Laboratory for High Energy Physics (LHEP) is a division of the Physics Institute at the University of Bern in Switzerland and is part of the Albert Einstein Center for Fundamental Physics. It conducts research in the field of experimental particle physics. |

2025/12/03