Empathy and cooperation in rats

Rats release trapped companions, subsequently enabling them to collaborate for acquiring food. Experiments conducted at the University of Bern established this connection between obliging liberation behaviour and coordinated cooperation. These results may point towards a biological basis for empathy, presenting new perspectives on the evolutionary origins of compassionate behaviour.

Previous behavioural studies have shown that lab rats may free trapped conspecifics from a tube in which they were confined for the experiment. This observation sparked scientific discussions about the capability of animals to show empathy. Many researchers interpreted it as evidence that animals might feel compassion for others in distress. However, an explanation of how this behaviour may have evolved was lacking.

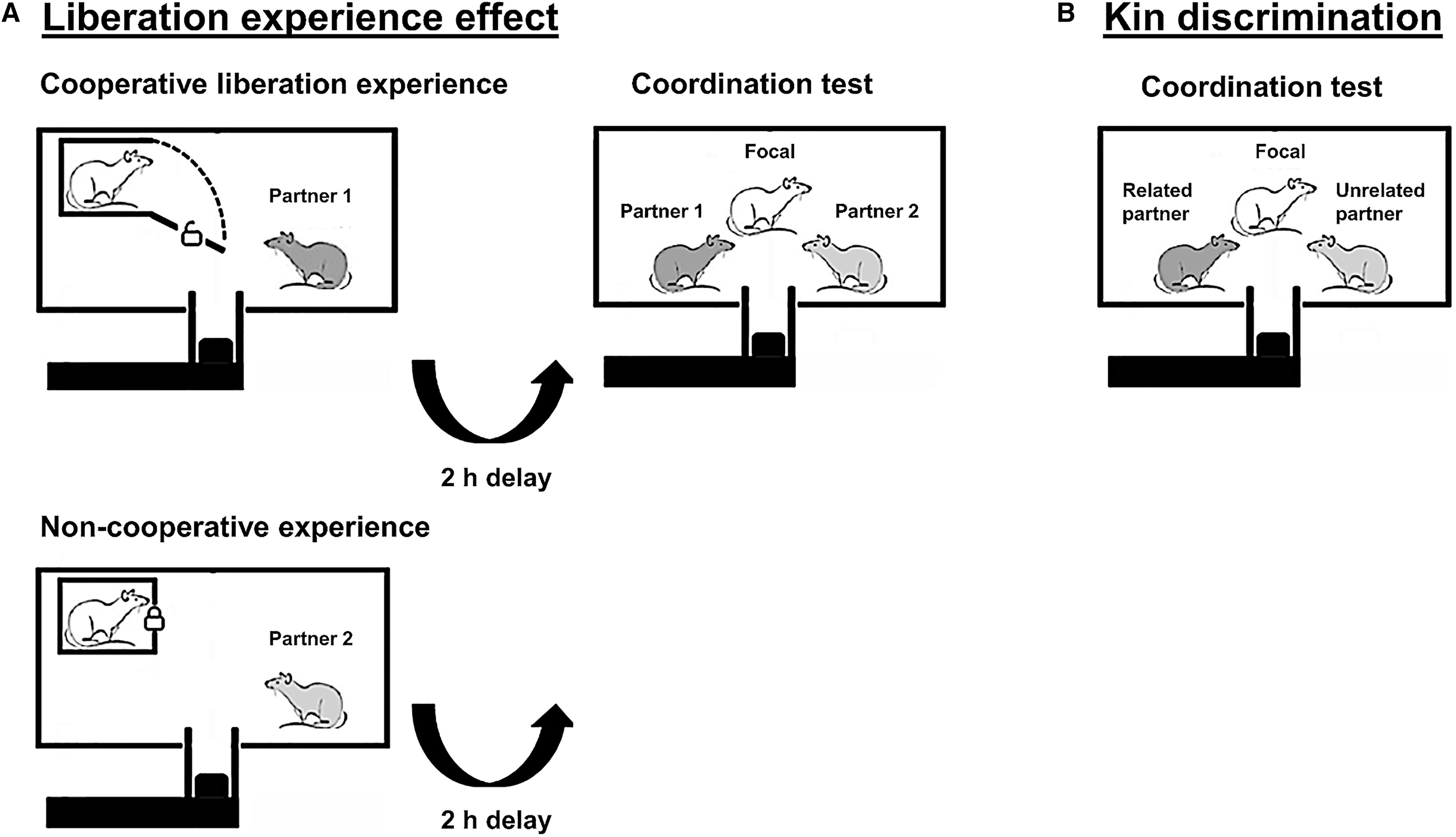

In a new study, a team from the Division of Behavioural Ecology at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern, investigated the potential benefits of freeing a peer: does it provide future cooperation opportunities, or is it primarily about aiding relatives? The goal of this study was to determine whether mutual dependence or kin selection could explain the evolution of seemingly altruistic liberation behaviour. The results show that rats freed by a peer later preferred to cooperate with their rescuer to jointly acquire food. This coordinated cooperation was driven by the prior help received, while kinship between the animals did not influence their propensity to collaborate. The findings have been published in the journal iScience.

Help those who helped you

The researchers replicated the original experiments showing that rats release conspecifics from a tube, but with a crucial extension. After being freed, the animals were given the opportunity to work together for acquiring food. The aim was to determine whether for obtaining food a rat that had been freed would preferentially cooperate with its rescuer, rather than with a peer that had not helped. The experiment yielded clear results: rats freed by another rat coordinated more readily with their rescuer in a challenging food acquisition task than with a non-helper. "This shows that reciprocal cooperation extends beyond specific tasks and contexts," explained Sacha Engelhardt, lead author of the study and former postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution.

Kinship is irrelevant

"Typically, we assume that the readiness to cooperate strongly depends on whether social partners are related," said Michael Taborsky, head of the study. Many previous studies of cooperative behaviour have suggested that collaboration in animals primarily occurs among related individuals. Therefore, the research group conducted an additional experiment to examine whether kinship influenced the rats’ willingness to cooperate in obtaining food. The results showed that kinship had no significant impact on cooperation. "Once again, rats exemplify that social experiences and received help are more critical for cooperation than genetic relatedness," said Taborsky. These new findings corroborate previous research from the group, which demonstrated that reciprocal help may work even better between unrelated animals than among kin. The findings confirm that the motivation to cooperate generally depends more on past social experiences than on shared genes.

Empathy as a product of natural selection?

The results of this study shed new light on potential biological roots of empathy. The fact that rats are more likely to cooperate with their rescuers suggests that helpful behaviour toward peers in distress can possibly enhance survival and reproductive success and may therefore be adaptive. "This might indicate that compassionate behaviour is promoted by natural selection, hinting at its biological basis. It also implies that empathy may not be a uniquely human trait," Taborsky concluded. Next steps should explore the neurobiological mechanisms of seemingly empathic behaviour and its prevalence among social animals in general.

Publication details:Engelhardt, S. C., Paulson, N. I., & Taborsky, M. (2024). Norway rats recruit cooperation partners based on previous receipt of help while disregarding kinship. iScience. |

About the Division of Behavioral Ecology, University of BernThe Division of Behavioral Ecology at the Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern, studies the evolutionary mechanisms underlying animal behaviour in relation to ecological and social conditions. Together with other divisions, it creates a scientific foundation for understanding and preserving the living environment. The division investigates how organisms respond to and interact with their environment, including phenotypic responses at the individual level, genetic changes at the population level, and the evolution of key elements of animal behaviour and social systems. More information |

2024/12/11