A thousand days of CHEOPS

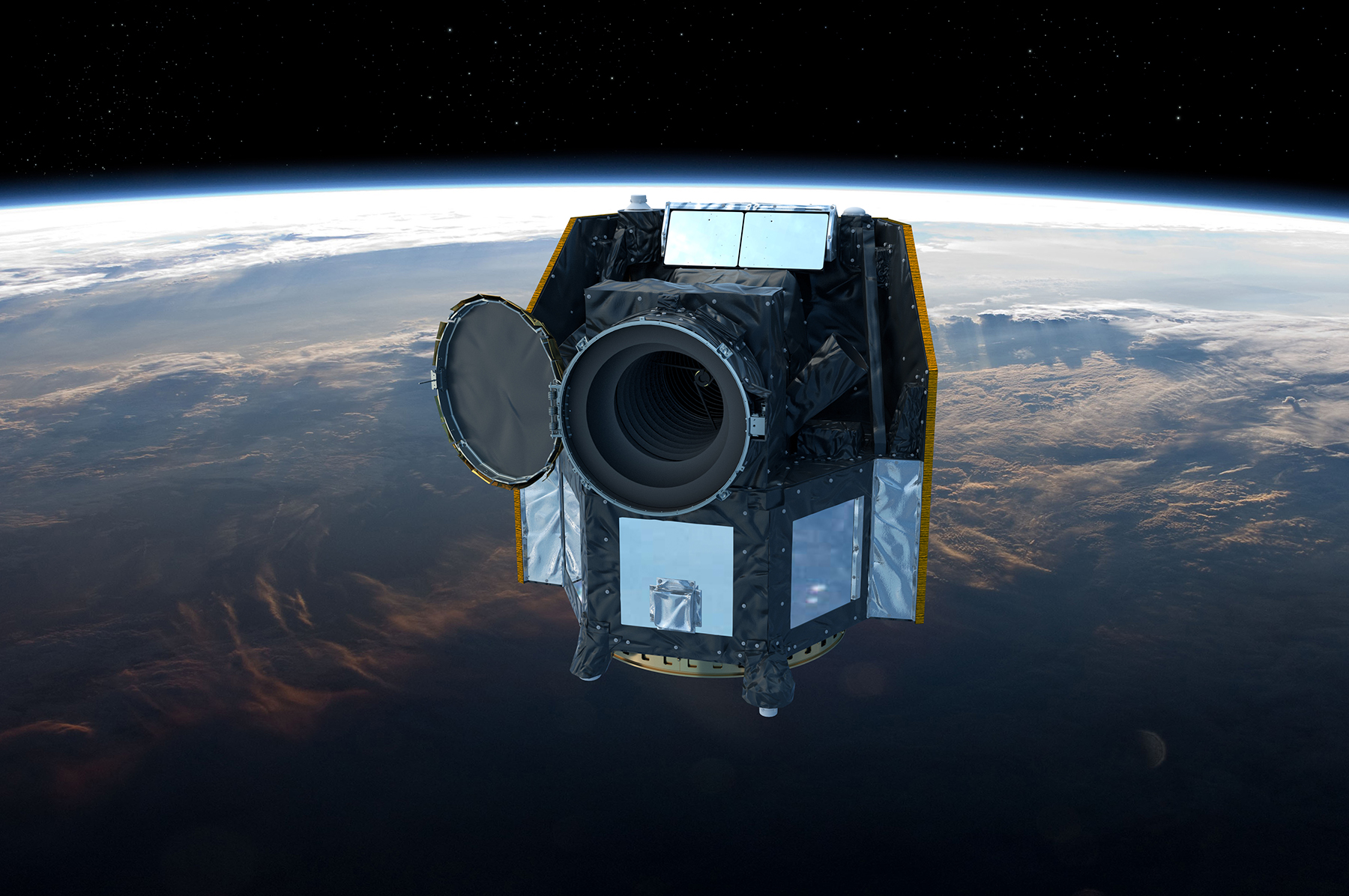

After a thousand days in orbit, the CHEOPS space telescope shows almost no signs of wear. Under these conditions, it could continue to reveal details of some of the most fascinating exoplanets for quite some time. CHEOPS is a joint mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Switzerland, under the aegis of the University of Bern in collaboration with the University of Geneva.

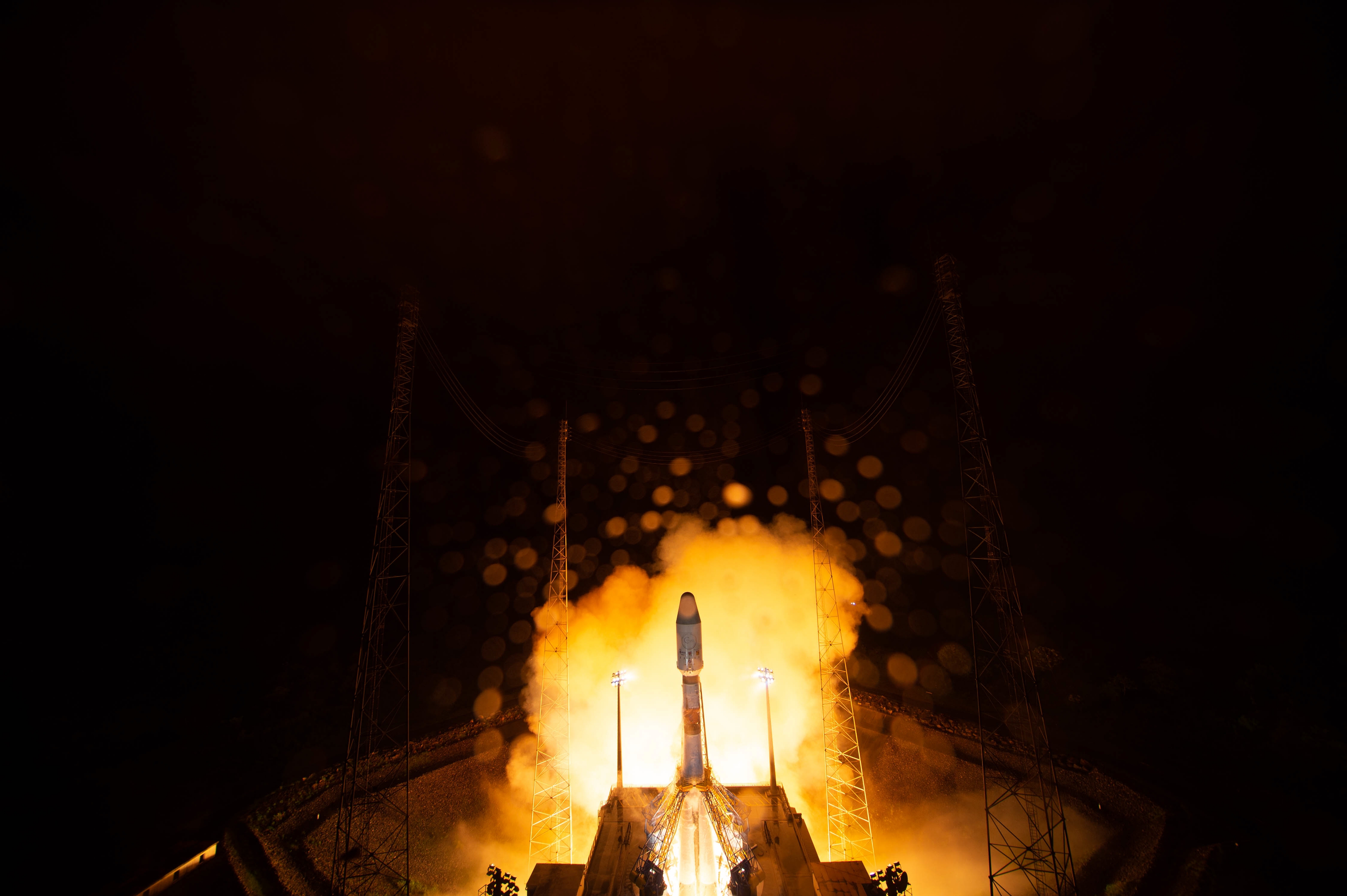

Since its launch from Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana, on December 18th, 2019, the CHEOPS telescope in Earth’s orbit has demonstrated its functionality and precision beyond expectations. During this time, it has revealed the characteristics of numerous fascinating planets beyond our Solar System (exoplanets) and has become a key instrument for astronomers in Europe and worldwide.

Enabling plentiful research across Europe

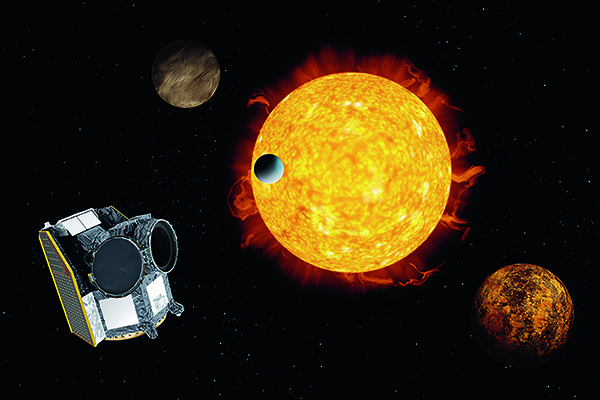

In over a million of minutes of observation time, CHEOPS has revealed exoplanets from every angle: their night sides when they pass in front of their stars, their dayside when they pass behind their stars and all the phases in-between, just like the Moon. “The precise data we collected from CHEOPS has borne fruits: over fifty scientific papers have been published or are in the process of being submitted by over a hundred scientists forming the CHEOPS Science Team and working at dozens of institutions all over Europe”, Willy Benz, Professor emeritus of astrophysics at the University of Bern and head of the CHEOPS consortium, reports.

This has been achieved without the possibility for international scientific team exploiting the instrument to meet physically due to the pandemic. Now, for the first time since the launch of CHEOPS, all involved scientists can finally meet in Padua, Italy, from 12 to 14 September. “It is the first time in three years that we can finally get together”, mission scientist David Ehrenreich and Professor of astronomy at the University of Geneva says. “It feels amazing to celebrate what we have discovered in 1000 days and discuss what we will do next.”

Findings include, for example, the characterization of blisteringly hot, iron-evaporating atmospheres on planets that are so close to their stars that they are deformed into rugby-ball shapes by the immense gravitational forces. “By detecting a system with six planets, of which five orbit their star in a fragile harmony, CHEOPS has also given us glimpses into the formation of planetary systems”, Ehrenreich says.

Just earlier this year, the space telescope once again demonstrated its astounding precision by measuring the faint light reflected by a planet located 159 light years away in the constellation Pegasus. “Although this planet, HD 209458b, is certainly the most studied exoplanet ever, we had to wait 22 years for CHEOPS and its amazing precision and dedication to be able to measure the visible light reflected from its atmosphere” Benz says proudly.

A valuable and durable asset

“Even after 1000 days in orbit, CHEOPS still works like a charm and only shows very small signs of wear, caused by energetic particles emitted by the Sun”, CHEOPS instrument scientist Andrea Fortier from the University of Bern says. Under these conditions, the researcher expects that CHEOPS could continue to observe other worlds for quite some time. “It will continue its mission around the Earth until at least September 2023 but the CHEOPS team is working with the European Space Agency and the Swiss Space Office to extend the mission until the end of 2025 and possibly even beyond”, Fortier says.

The capabilities of CHEOPS could continue to serve the scientific community well, even now that the James Webb Space Telescope is in operation. “We are convinced with its high precision and flexibility, CHEOPS can act as a bridge between other instruments and Webb, as the powerful telescope needs precise information on potentially interesting observation targets. CHEOPS can deliver this information – and thus optimize the operation of Webb”, Willy Benz points out. This is already happening, as the Webb telescope will observe, later this year, several systems highlighted by CHEOPS.

CHEOPS – in search of potential habitable planetsThe CHEOPS mission (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite) is the first of ESA’s newly created “S-class missions” – small-class missions with an ESA budget much smaller than that of large- and medium-size missions, and a shorter timespan from project inception to launch. CHEOPS is dedicated to characterizing the transits of exoplanets. It measures the changes in the brightness of a star when a planet passes in front of that star. This measured value allows the size of the planet to be derived, and for its density to be determined on the basis of existing data. This provides important information on these planets – for example, whether they are predominantly rocky, are composed of gases, or if they have deep oceans. This, in turn, is an important step in determining whether a planet has conditions that are hospitable to life. CHEOPS was developed as part of a partnership between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Switzerland. Under the leadership of the University of Bern and ESA, a consortium of more than a hundred scientists and engineers from eleven European states was involved in constructing the satellite over five years. CHEOPS began its journey into space on Wednesday, December 18, 2019 on board a Soyuz Fregat rocket from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. Since then, it has been orbiting the Earth on a polar orbit in roughly an hour and a half at an altitude of 700 kilometers following the terminator. The Swiss Confederation participates in the CHEOPS telescope within the PRODEX programme (PROgramme de Développement d'EXpériences scientifiques) of the European Space Agency ESA. Through this programme, national contributions for science missions can be developed and built by project teams from research and industry. This transfer of knowledge and technology between science and industry ultimately also gives Switzerland a structural competitive advantage as a business location – and enables technologies, processes and products to flow into other markets and thus generate added value for our economy. More information: https://cheops.unibe.ch |

Bernese space exploration: With the world’s elite since the first moon landingWhen the second man, "Buzz" Aldrin, stepped out of the lunar module on July 21, 1969, the first task he did was to set up the Bernese Solar Wind Composition experiment (SWC) also known as the “solar wind sail” by planting it in the ground of the moon, even before the American flag. This experiment, which was planned, built and the results analyzed by Prof. Dr. Johannes Geiss and his team from the Physics Institute of the University of Bern, was the first great highlight in the history of Bernese space exploration. |

Exoplanet research in Geneva: 25 years of expertise awarded a Nobel PrizeCHEOPS provides crucial information on the size, shape, formation and evolution of known exoplanets. The installation of the "Science Operation Center" of the CHEOPS mission in Geneva, under the supervision of two professors from the UNIGE Astronomy Department, is a logical continuation of the history of research in the field of exoplanets, since it is here that the first was discovered in 1995 by Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, winners of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics. This discovery has enabled the Astronomy Department of the University of Geneva to be at the forefront of research in the field, with the construction and installation of HARPS on the ESO's 3.6m telescope at La Silla in 2003, a spectrograph that remained the most efficient in the world for two decades to determine the mass of exoplanets. However, this year HARPS was surpassed by ESPRESSO, another spectrograph built in Geneva and installed on the VLT in Paranal. CHEOPS is therefore the result of two national expertises, on the one hand the space know-how of the University of Bern with the collaboration of its Geneva counterpart and on the other hand the ground experience of the University of Geneva supported by its colleague in the Swiss capital. Two scientific and technical competences that have also made it possible to create the National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS. |

2022/09/12